Dakshinamurthy

The Benign Imagery in Indian Temples

By Soumya Manjunath Chavan

The concept of Dakshinamurti mentioned in the Rig Veda was the transformation of Rudra into the giver of gifts. The Dakshinamurti Upanishad elaborates on the aspect of medha Dakshinamurti imparting knowledge to the rishis. The hymn of Dakshinamurti of Shankara gives an elaborate description of him with myriad epithets of the essence of the characteristics of a Master falling in line with the Guru of Upanishads and unfolding in beautiful poetic imagery. These metaphors of the great teacher, claimed to be the first and having initiated the Rishis of the highest order with the knowledge of the ultimate Brahman. This explicit imagery of Dakshinamurti is reflected in the ritual and art, thus, creating a prominent niche in the wide canvas of Indian art and culture. The cult of Śiva known as Śaivism is one of the oldest faiths in the world and most widely spread in India. Śiva means ‘in whom all things lie’, and connected to auspiciousness, propitious, gracious, favourable, benign, kind, benevolent and friendly. The third among the Hindu Trimūrti, and in the Veda he was known as Rudra ‘the terrible god,’ the destroying deity but in the later times it became usual to give that god the euphemistic name Śiva ‘the auspicious one’. Śiva is identified with the symbolic form of Linga and the anthropomorphic forms like Bhairava, Natāraja, Vīrabhadramūrti, Umāmaheśwara, Daksināmūrti etc.

Rudra becoming the giver

Addressed as Raudra Brahman or Wild God in the Rg-veda, he transforms into the saumya forms representing sadguna related with Śiva as a teacher. This transformation of Raudra Brahman into Daksināmūrti as observed in the Rg-vedic hymns narrates that Manu had divided his property among his sons, but nothing was left for his youngest son, Nābhānedistha. Hence Manu advised his son to proceed to the sacrifice of the Angirasas and lead them to heaven by singing the mantras of the Raudra Brahman and receive their thousand cows in return. Just as Nābhānedistha was collecting the cattle, a large man from the north clothed in black, stopped him, saying, “this is mine; mine is what is left at the site.” On knowing the truth from his father that An۟girases did not have the power to dispose of the cattle, Nābhānedistha returned the cattle to the stranger who was Raudra Brahman himself. Pleased with Nābhānedistha, who spoke the truth, Rudra gifts the cattle back to him. This gift or daksinā was the first ever given to an inspired seer and a prototype for every daksinā or present given to a priest at the completion of a sacrifice. This image of Rudra as a giver of daksinā came to be called as Daksināmūrti.

Daksināmūrti – the meaning

The root daks meaning, to be able or strong and Daksinā means able, clever, straightforward, donation to the priest, to place anyone on the right side as a mark of respect, south and southern. The Daksināmūrti Upanisad, which is in a dialogue format between Śavanaka sages and Mārkandeya, gives a clear imagery and salient features of Daksināmūrti.

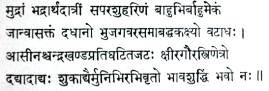

May the milk-white three-eyed Primal Being grant us purity of thought

He who, seated at the foot of a fig tree, surrounded by Śuka and other sages

Holding in the hands the symbol, the blessed wisdom, with axe and deer

One of the hands resting on the knees, the lion girdled round by a mighty serpent,

A digit of the moon enclosed in His clotted hair

Lord Shiva, in order to instruct the rishis and the seers assumed the form of a guru, and sitting on the peak of Kailasa. He turned southward to serve all seekers. The term Dakshinamurti means “that divine power of subtle perception which is generated in a fully integrated pure intellect”. He is the Supreme God who, at the end of an aeon (kalpa) absorbs within himself the whole universe and remains resplendent in joy. He is seen seated on a raised platform placed under a banyan or fig tree, his left leg bent and rested upon the seat and his right one rests on the Apasmāra-purusa who is the personification of ignorance; on his head is the jatābandha; the back right hand holds a snake and the front right hand holds an aksamālā and is in the chin-mudrā; the back left hand carries a bundle of kuśa grass, the front left hand carries an amrta-ghata. He wears round his lions a garment; deer skin worn in the upavīta fashion, he has a resplendent face and a calm radiant smile; He is seen surrounded by sages and disciples sitting around him.

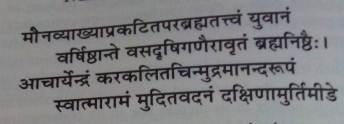

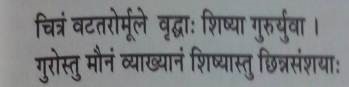

Dakshinamurti – The Guru who taught through Silent eloquence

The benign form of Dakshinamurti is described by Sankara in two stanzas of his Dakshinamurti stotra. At one instance, he expresses awe and paints the verbal picture as: calling it strange that under the banyan tree were the aged disciples around the youthful guru! He taught them with “silence” but doubts of the disciples were all dispelled. In yet another hymn Shankara states that he worships Dakshinamurti who is a young guru, teaching the knowledge of Brahman through silence to the rishis and scholars in the Veda-s, who is the teacher of teachers, whose hand is held in the “sign of knowledge”, whose nature is bliss who ever revels in His own Self, and who is ever silent. This uniqueness of Dakshinamurty who imparts the knowledge of the Brahman to the rishis without a single spoken word becomes an important characteristic of the iconography and poses as a challenge to the artist to paint and sculpt the image of Dakshinamurti potent with knowledge but imparting in silence.

Forms of Dakshinamurti

Daksināmūrti is of four different aspects namely, Yoga-Daksināmūrti as a teacher of yoga, Vīnādhara-Daksināmūrti as a great teacher of music, both instrumental and vocal and other arts, Jnāna-Daksināmūrti as the preceptor and one who imparts enlightenment, Vyākhyāna-Daksināmūrti as an expounder of other Śāstras. The image called Daksināmūrti with its unique attributes of a teacher imparting the highest knowledge finds a significant place in the Indian art and Temple Architecture.

Daksināmūrti in Indian temple architecture

The craftsman goes through the whole process of self-purification and worship, mental visualisation and identification of consciousness with the form evoked and then only translates the form into stone or metal. Thus, the trance formulae become the prescriptions by which the craftsman works and as such they are commonly included in the Śilpa Śāstras, the technical literature of craftsmanship . To embellish form the artist uses decorative treatment, to bring serenity in form he may take up divine approach, to beautify the form he searches parallels in nature, to get a vicarious pleasure he distorts the form or to obtain an empowering form he exaggerates the normal form by filling up with strength and vigor. The imagery of Daksināmūrti in Indian temples from the walls of the sanctum, the panels along the circumambulatory path, the pillars and the gopuras of the temple complexes are analyzed and discussed in a similar line of thought, elucidate form of Daksināmūrti as serene, empowering, beautiful and decorative.

Daksināmūrti adjacent to the Sanctum – Mahakaleshwar Jyotirlinga is situated below ground level of the Garbhagriha in the main temple. The idol of Mahakaleshwar being a linga facing the south is known to be Dakshinamurti. This is a unique feature upheld by tantric traditions found only in Mahakaleshwar among the 12 Jyotirlingas. The Daksināmūrti which is in a contemplative posture and imparting gestures is housed in a small niche or a small mantapa adjacent to the sanctum. Most of the navagraha temples, which were visited and documented in Tamil Nadu, have a small shrine dedicated to Daksināmūrti adjacent to the sanctum. Of which fine examples were found in the Alangudi, the Guru temple, Thingalur, the Candra temple and Kezhaperumpallam, the Ketu temple (fig 1) along with Nataraja temple, Chidambaram (fig 2) and Brhadiśvara temple of Tanjore (fig 3). The forms of Daksināmūrti in all these temples are serene and similar to that of Vyākhyāna-Daksināmūrti as an expounder of other Śāstras. His body composed of eternal bliss and sitting in vīrāsana , the spread of the banyan tree symbolic of māyā (illusion) with his attributes of snake, lotus and a book or aksamālā, and the āpasmārapurusha under his right leg. This form of Daksināmūrti finds its similarity with the description given by Śankara in his Daksināmūrti Stotram, which says,

Daksināmūrti panels on the walls of Temples – The panels on the South side of the temple are elaborate and of a descriptive quality and are spread on a larger space compared to the Daksināmūrti images discussed earlier. The composition is divided into three portions with the eye catching central space dedicated to Daksināmūrti flanked by smaller divisions complemented by a number of images. As an interesting example, the Daksināmūrti panel in the Airavatehswara temple at Darasuram has four pillars which divide the space into three portions. The central niche has Daksināmūrti seated in all calmness and imparting gestures and flanked by two panels on either side which are host images which look like sages, human forms and dwarfs with varied expressions. The Daksināmūrti panel in the Kailasanatha temple at Kancipuram is of similar division of space with three portions and the central niche dedicated to Daksināmūrti and flanked by lions and sages. The description about Daksināmūrti given in the Śivanidhi helps in relating to this panel and identifying the images flanking Daksināmūrti.

Daksināmūrti of white complexion of sacred ash carries the crescent moon on his head, his hands have gestures of knowledge, a rosary, a lute and a serpent and sacred staff called Yogapatta. He sits on a seat called Vyākhyāna pītha and is surrounded by all great sages and is of a calm temperament. He is adorned by serpents and wears the skin of a deer and is very auspicious. Seated under a banyan tree in the Mount Kailāsa, on the right he is flanked by Jamadagni, Vasistha, Bhrgu and Nārada and on the left are Bharadvāja, Śaunaka, Agastya and Bhārgava. The names, of the sages and forms around Daksināmūrti vary from text to text.

Daksināmūrti on Temple Pillars – Daksināmūrti depicted on the pillars are smaller in size and exhibit movement in the image, which seems to be responding or alive. The Daksināmūrti on a pillar opposite the Meenakshi Sundareshwara temple in Madurai is a very good example of this to life image. This image of Daksināmūrti sitting in all its majesty looks downward with a rare smile radiating compassion. It is observed in Chidambaram, Nataraja temple and the Guru temple in Alangudi the Daksināmūrti on the pillar is not facing the south but is facing the north. These two images of Daksināmūrti are also very expressive and in the mood of imparting knowledge.

Daksināmūrti depicted on the Gopuras – The temple towers act as galleries exhibiting a variety of gods, goddess and human figures along with animal figures in the entrances of temples. These are narrative, sometimes colourful and decorative. The Gopuras of some of the temples like Nataraja temple, Chidambaram, Brihadeshwara of Tanjore, Arunachaleshwara of Tiruvannamalai exhibit Daksināmūrti on the southern walls of the gopuras in his various forms like Vyākhyāna-Daksināmūrti, Yōga-Daksināmūrti, Vīnādhara-Daksināmūrti and jnāna-Daksināmūrti.

Conclusion

Daksināmūrti represented in the temple architecture forms a unique imagery in different locations of the temples. Adjacent to the sanctum, Daksināmūrti is in a contemplative mood at the same time is symbolic of imparting knowledge through silence whereas the panels on the outer walls of the temples are more elaborate, narrative and the image of Daksināmūrti in a teaching posture gains some movement suggested by his curved body and turned head as though he seems to turn around and look at His disciples sitting and listening with awe-struck expressions. The images of Daksināmūrti on the pillars express some interactive movement through the slightly raised hands and the posture of the body. The towers are exemplary galleries which exhibit the variety of Daksināmūrti at layers differing from three to seven in different temples and from a distance it draws the immediate attention of passers by and people entering the temple. Thus the image of Daksināmūrti as a teacher of the highest knowledge finds a place of great significance at every enclosure of Śaiva temple complexes exhibiting the majesty of his silence transforming into an expression of the visual imagery communicating the celebration of gnosis through philosophy and art. The representation of Śiva in his contrasted and diversified forms as a loving spouse, an empowering dancer and the first guru who transmitted the knowledge of gnosis through silence has opened the panoramic stage for thinkers of art and aesthetics to understand, contemplate, experience, rethink and interpret the imagery of Śiva in its myriad dimensions.

End Notes

1. Rao, Ramachandra, SK, 1994, Art and Architecture if Indian Temples, Volume one, p-103, Kalpataru Research Academy, Bangalore

2. Rao, Gopinath, TA, 1997, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol II, part I, p-1, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

3. Williams, Monier, 1963 – 99, A Sanskrit English Dictionary, p-1074, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

4. Kramrish, Stella, 2007, The Presence of Śiva, p-3, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

5. Dwivedi, Kant, Shiva, 1991, Temple Sculptures of India, P-98, Agamkala Prakashan, Delhi

6. Kramrish, Stella, 2007, The Presence of Śiva, p-55-57, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

7. Williams, Monier, 1963 – 99, A Sanskrit English Dictionary, p-465, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

8. Subbramaiya, DS, Sri Dakshinamurti Stotram, Vol II, Daksināmūrti Upanisad, p 589-11, Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri

![]()

9. Chinmayananda, Swami, commentary, Hymn to Sri Dakshinamurty of Adi Sankara, p-5 Central Chinmaya Mission Trust, Mumbai, 2011

10. Rao, Gopinath, TA, 1997, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol II, part I, p-279, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

11. Chinmayananda, Swami, commentary, Hymn to Sri Dakshinamurty of Adi Sankara, p-9 Central Chinmaya Mission Trust, Mumbai, 2011

12. Chinmayananda, Swami, commentary, Hymn to Sri Dakshinamurty of Adi Sankara, p-8 Central Chinmaya Mission Trust, Mumbai, 2011

13. Rao, Gopinath, TA, 1997, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol II, part I, p-273-289, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

14. Coomaraswamy, Ananda, K, The Origin and Use of Images in India, p-91 http://prakashan.vivekanandakendra.org

15. Nandagopal, Choodamani, Kalā – The journal of Indian Art History Congress, Vol:XVII 2011-2012,p-29, Indian Art History Congress, Guwahati, Assam, India.

16. Vīrāsana – right leg should be hanging below the seat while the left on is bent and rested across on the right thigh

17. Wodeyar, Śri Mummadi Krsnarāja, Śrītattva-Nidhi (Vol 3) Śivanidhi p-180, Oriental Research Institute,

18. Mysore, 2004

Books and References

• Coomaraswamy, Ananda, K, The Origin and Use of Images in India, http://prakashan.vivekanandakendra.org

• Chinmayananda, Swami, commentary, Hymn to Sri Dakshinamurty of Adi Sankara, Central Chinmaya Mission Trust, Mumbai, 2011

• Dwivedi, Kant, Shiva, 1991, Temple Sculptures of India, Agamkala Prakashan, Delhi

• Kramrish, Stella, 2007, The Presence of Śiva, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

• Nandagopal, Choodamani, Kalā – The journal of Indian Art History Congress, Vol:XVII 2011-2012, Indian Art History Congress, Guwahati, Assam, India.

• Rao, Gopinath, TA, 1997, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol II, part I, p-1, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

• Rao, Ramachandra, SK, 1994, Art and Architecture if Indian Temples, Volume one, Kalpataru Research Academy, Bangalore

• Subbramaiya, DS, Sri Dakshinamurti Stotram, Vol II, Daksināmūrti Upanisad, Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri

• Williams, Monier, 1963 – 99, A Sanskrit English Dictionary, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited, Delhi

• Wodeyar, Śri Mummadi Krsnarāja, Śrītattva-Nidhi (Vol 3) Śivanidhi Oriental Research Institute, Mysore, 2004