Art is the mirror of culture. The stages of human development find the path of refinement through the emancipation of culture. Through art, this fine cultural expression sustains human spirit in all the ages — past, present and future. Thus, Indian art, thought, and literature have focused on the concept of unconscious to conscious through which the seeker aspires to attain bliss; in Indian understanding, it is atmananda (joy of the soul). From time to time, Indian philosophy has tried to link abstract concepts such as space in terms of existence, time in terms of experiencing bliss, and thought in terms of consciousness. Out of such philosophical thought emerged the idea of creating the image proper, concentrating in it all the abstract properties. In this process, the formless — a unique concept — has transformed itself into an embodiment of magnificent expression in the form of sculpture. In this way, sculpture or Shilpa is three-dimensional art expressing the concrete form of divine beings.

The evolution and development of Indian sculpture is unique, and every period of Indian history is reflected through sculpture that was created by master artisans. Thus, through Indian sculpture one can connect to the historical past with authenticity. Though we do not have evidence of sculptural representation from the Vedic period, the passages and hymns in Vedic literature describing the Vedic Gods, such as Indra, Rudra, Agni, Varuna, and Prajapati have an impact on the image makers of later times. New research on Indus-Sarasvati Valley Civilization is establishing the continuity between Vedic and Indus Civilization.

.

Qualitative Insight:

From terracotta figurines of the Indus Valley, to the expressive stone and metal images of medieval times, Indian sculpture has evolved into a major art form with almost every century contributing fresh styles of expression. The puranic incarnations of Vishnu emerged as mighty figures in the Gupta period as a divine boar in the Udayagiri and Dashavatara caves at Ellora of Rashtrakuta times. Similarly, the abstract form of linga reveals itself in the anthropomorphic forms of Shiva, reaching the height of manifestation in Chalukya, Pallava, and Rashtrakuta art. The Maheshamurthi in the Elephanta caves represents the pinnacle of human creative expression wherein the human hand and touch could transform the formless into a divine form.

The expression of spiritual qualities and the sense of attainment of salvation reached the height of idealization in the form of the Buddha and Tirthankara (one who has conquered samsara, the cycle of death and rebirth) images. The quality of Indian sculpture exists in the timeless being, simply at rest within its fullness, surrounded by silence. The essence of dance, music, spirituality, functional objectivity, and surrendering sublimate are faithfully rendered in the sculptural art of India.

When we observe the sculptures and paintings created from pre-historic to contemporary times, it is evident that at any given point of time Indian art is expressed with higher emphasis on the depiction of female figures. The renowned art historian Stella Kramarisch is completely right in her opinion: “Indian art culminates in the representations of feminity”. The feminine form has caught the interest of artist and devotee alike, who never tire of creating or viewing the female form in all its manifestation.

Evolution and Development of Indian Sculpture

India has a rich heritage of sculpture stretching from the Indus period to that of the Vijayanagar Empire (fourteenth to seventheenth centuries C.E.). The different styles of sculpture are influenced by the ruling dynasty at the time of the creation of the respective sculpture. The style of sculpture reflects the changing trends of the culture. A brief review of the sculpture created in different eras provides information regarding the patronage endowing the sculpture of the time, each period’s genres, and the overall contribution of the art of each respective period to the art of Indian sculpture as a whole.

Early Period

The earliest extant Indian sculpture dates from the Indus-Sarasvati Valley period (2000 B.C.E.). The favorite material for creating art objects during the Indus Valley civilization was terracotta. The terracotta art in the Indian subcontinent goes back to a very early period of human history. Even today, it continues to be an appealing medium for Indian artists. The quantity and quality of specimens are remarkable at many of the Indus Valley sites.

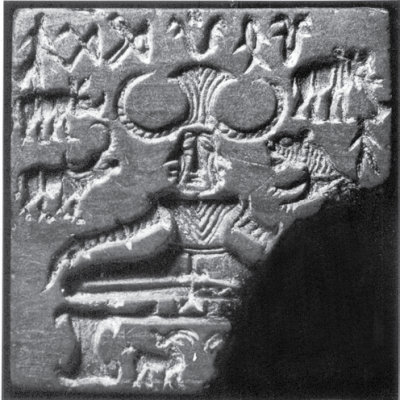

Indus Valley civilization sculpture consists of two types of carving: seals and art objects. The seals were used for trade, and 3200 have been found so far. The carving on the seals is low-relief. Different animals, human figurines, and writing are engraved on the seals. With the discovery of a large number of seals, it is clear that the Indus people used alphabetic writing and ideas of other type are rounded. The seals are of different sizes and shapes, such as rectangular, square, triangular, round, and semi-circular. They are made of different materials such as clay, terracotta, soft stone, and faience. The Indus Valley seals and sculptures are highly stylized. The art objects are items of daily use, such as pottery and jewelry, which were used in urban and rural areas. Cross-cultural influences are apparent in these carvings, as well.

Indus Valley art has the basic feature of simplicity when compared to the complicated processes of later Indian art styles. The animal and human figurines are well modeled in stone, terracotta, and bronze with a naturalistic treatment of body elements. One of the centerpieces of Indus Valley art is the image of the mother goddess. The concept of the mother goddess still predominates as the guardian of the house and villages in India, presiding over childbirth and daily needs. The Grama Devata (tutelary deity of every village) tradition is very much part of the present day life in Indian towns and villages. Several manifestations are associated with the Grama Devata concept. The presence of mother goddess sculptures in all phases of Indus Valley civilization makes it clear that mother goddess was a popular cult of the Indus Valley, but not in the southern and eastern provinces of the Indus Empire. The mother goddess figurines are numerous at Harappa and Mohenjodaro, but absent in Kalibangan, Lothal, Surkotada, and Dholavira.

Mauryan Sculpture

The Mauryan period marks an imaginative and impressive step in Indian sculpture. The literature of the period mentions the artisan guild (registered group) who worked on the Emperor Asoka’s projects. The Emperor wanted to articulate Buddhism in stone. He declared himself to be the protector of dharma (duty, natural laws, or righteous living among other definitions). He used Pali and Brahmi script for issuing the edicts. To know about the Mauryan sculptural art, we have to study:

- decorations of the Mauryan capitals,

- rock-cut caves and sculptures,

- rounded sculptures and images, and

- ring stones and disc stones.

Apart from these, wood was also preferred to create art objects and structures.

Life-size images of yaksha (nature spirits) and yakshi (feminine nature spirits) are the centerpieces of Mauryan art. There are a variety of art objects created in this period which include pillars, railings, parasols (stone umbrellas), pillar capitals, monolithic columns, jewelry, animal and human sculpture, and other objects and motifs. One of the important features of Mauryan art is the bright polish imparted to the stone’s surface. The mirror-like polish transforms the ordinary stone to a superior material. Ashoka’s imperial status was effectively brought out by the sculptors. Thus, the works of art portray the attitude of Asoka toward his kingdom and Buddhism. The forms of sculptures are typical, and the content was most suitable to the material.

The Kushan rulers made outstanding achievements in art. Gandhara was located in the center of Kushan Empire. It was a trade capital, and meeting place for the merchants who traveled on the Silk Road. Kanishka introduced images of the Buddha into his empire. These images were made in Gandhara with heavy Greco-Roman influence. Similarly, Buddha images were created by Indian sculptors in Mathura.

Gandhara School : Stylistically, Gandhara sculpture is Greco-Buddhist. The distinguishing feature of Gandara art is that it is extremely fine, realistic, and expressive. The Buddha and Bodhisattva (a person whose aim it is to be enlightened for the benefit of all sentient beings) sculptures display a sophisticated iconography in an advanced style. The Gandhara sculptures depict the earliest representations of the Buddha. Many plaques are high relief depictions of the events of the Buddha’s life. The carvings are done in soft stone. In the Mathura school, the relief is higher than that of the Gandhara school. In the Amaravati style, the relief sculptures are more artistic because of the stone used. Creamy, white limestone was used for the plaques on Amaravati stupas (a mound or hemispheric structure containing relics). We will study more about it under stylistic features

Much sculpture in the round, or freestanding sculpture, was created in the Gandhara and Mathura centers of art. Colossal statues were made to show the imperial status and power of Buddhism, and to depict the rulers of Kushan dynasty. There are also many Buddha and bodhisattva figures. In the Amaravati School, there is very little sculpture in the round.

In Gandhara sculpture the Buddha is depicted standing or seated. The seated Buddha is always shown cross-legged in the traditional Indian way. Another typical feature of Gandhara sculpture is the rich carving, elaborate ornamentation, and complex symbolism. The aesthetic quality of the Gandhara Buddhas is different from that of the Mathura Buddhas. The Gandhara Buddha and bodhisattva figures resemble the Greek god Apollo: with broad shoulders, and a halo around the head — more a powerful hero than a yogi (practitioner of yoga). The dress of the Buddha is carved realistically with many folds. The physical features such as muscles, nails, and hair are shown in great detail. The drapery, heavy ornamentation, and moustaches featured on the images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas are far different from Indian idealism.

Mathura School: Like Gandhara, Mathura also was a great center of art and culture during the Kushan Empire. In Gandhara art, there is a strong Greco-Roman influence. In Mathura art, the important religions of India, such as Brahmanism, Jainism, and Buddhism are represented. It is believed that the first Buddha images were carved at Mathura during the same period in which those of Gandhara were created. Mathura has produced Buddha images of various dimensions.

The Mathura style evolved with native spirit and elements. On the railings of the stupas, there are quite a number of female figures — beautifully attired according to Indian taste. Mathura sculpture is denoted by a peaceful atmosphere. The features are more naturalistic than realistic. The elements are derived from the typical ideal of the Indian yogi — namely the lotus feet and the meditative gaze. Mathura artists rejected realistic Greco-Roman features, instead choosing naturalistic details to complete the sculptures. The entire figure was cloaked in refinement. The workshop of Mathura exported several Buddhist images to various places, such as Sarnath, and even as far as Rajgir in Bihar.

Amaravati School: During the Shatavahana period, a pre-eminent aesthetic movement developed in Andhra Pradesh — the Amaravati School. Several stupas adorned with refined carvings of exceptional beauty are characteristic of this period. The sculptures belonging to Amaravati School are found at sites in the valley of Krishna, and in museums in Jaggayyapetta, Amaravati, and Nagarjunakonda. The British Museum in London, and the Government Museum in Chennai house collections of stupa plaques from this period.

Amaravati style is elegant and sophisticated. The sculptured panels of Amaravati are characterized by a delicacy of form, and linear grace. Adorning these reliefs are numerous scenes of dance and music with joie de vivre in full display. The sculptural remains of Amaravati — known as the ‘marbles’ — are of white limestone. The carvings create the illusion of having been carved of marble, and even today are as fresh as when they were carved. As Buddha had chosen the new path of freedom, the artists of Amaravati School have chosen their own style, and freely expressed their artistic abilities.

Gupta Sculpture

The Gupta Empire (320 to 550 C.E.) is considered the Golden Age of India. Art in the Gupta period achieved classical status. Many texts were written and used as models for creating art. The dynasties ruling after the Gupta age in north and south India imbibed the artistic elements of the Golden Age, They continued the tradition of the delicate folds of the transparent garments adorning the Gupta figures. The Buddhist images of Mathura and Sarnath are some of the best specimens of Indian art, never equalled by art of later periods. Gupta sculpture can be found:

- in the Udayagiri rock-cut caves (Vishnu sculptures)

- at the Dhamek stupa at Sarnath, Bhitargaon,

- at the Buddhist caves in Ajanta, Ahichchattra, and

- at the Dasavatara Temple in Deogarh.

The profusely decorated halo is another special feature of the art of the Gupta figure. The relief work reaches its highest perfection here.

The delicate modeling of forms in meditative repose has rendered the Buddha and bodhisattva figures of the Gupta period most attractive. The Gupta figures are carved with elaborate ornamental details which make the divine figures very special in appearance. The art of terracotta and casting figures in stucco reached its zenith in this period. The clay figurines are on a small scale, whereas the stucco figurines in are much larger. The terracotta figurines were used in the brick temples. These figurines were of great variety and beauty. Gupta art is beautiful in both outer form, and inner inspiration. Beauty and virtue served as ideals of the age. Refinement was the order of the day. Decoration was the necessary feature of the Gupta sculpture. But the artists never over-decorated their figures or images. They maintained harmony of decoration, form and content — the best quality of good art.

Post-Gupta Sculpture

The post-Gupta phase of sculptural art — the ninth to the twelfth centuries C.E. — comprises Maitrakas of Vallabhi, Gurjara, Pratihara, Pala, Sena, and Chandela regions. These regions include present-day Gujarath, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, and Orissa. During this phase the regional styles each contribute a unique style in Indian sculpture.

Pala art was of superior quality in regard to image making. The famous Nalanda University flourished from the third to thirteenth centuries C.E., and was the center for the development of Pala art which influence extends to Southeast Asia. Over time Pala temples were destroyed or decayed. Sculpture originally from these temples is found in Nalanda, Bodha-Gaya, Rajashahi, and other places in Mayurbhanj area. Buddhist sculptures of Mahayana and Vajrayana themes are emphasised in Pala art. In later Pala phases Hindu sculpture comes into its own with superb workmanship, advanced technique, a chiseled quality, and a fine rendering of themes and iconography. Vishnu and Surya images in the Pala style are of exceptional quality. The Sena art followed the Pala principles and styles with refinement in treatment of figures, and detailing of the decorations and jewelry. The sculptural art of this phase is found in the Sun Temple at Modera, Udayeshvara Temple near Gwalior, Vimal, Vastu-pala, Teja-pala, Temples at Mount Abu, and some of the carved victory towers. Unfortunately, the decay of the material used, and the invasions of the Muslim rulers devastated the major architectural edifices of Pala and Sena. As a result, Pala sculpture is found today largely in museums — both in and and outside India.

The famous king Raja Mihir Bhoja — whose works Shrngara Prakasha and Samaranganasutradhara are the major sources for understanding medieval Indian art and aesthetics — was part of the The Gurjara-Pratiharas dynasty that ruled in north central India in the mid-seventh to eleventh centuries. The massive temple and sculptural art of Bhojpur, and the brick temple of Laksmana at Sirpur in Chattisgarh, have fine sculpture created with an outstanding image making technique.

Kalinga Style of Sculpture

The state of Orissa contributed to the development of Indian sculpture. The architectural grandeur of the Kalinga style is on display at Parasuramesvara, Raja Rani Temple, Muktesvara, Lingaraja, Sun Temple Konark, and Puri Jagannath Temple. The temple sculpture shows the gradual development of Orissan art and architecture. In Orissa, the architecture is of the north Indian Nagara style, with simple shikhara pattern to elaborate shikhara models, a simple pillared hall to elaborate natya mantapa, a dancing hall. The sculptures of these temples are life-size, exuberant, enormous, multiplying, of fresh subjects and rare compositions; the emphasis was on fine craftsmanship based on the texts and canons.

Candela Sculpture

The Candelas have occupied a unique position in the medieval art and architecture of India. They ruled in Madhya Pradesh from their capital Khajuraho. Thirty temples dedicated Siva and Vishnu and few Jaina were constructed during their reign of a hundred years (950-1050 C.E.) The Khandariya Mahadeo Temple is a masterpiece both from a sculptural and architectural viewpoint. Scholars are of the opinion that the Candelas followed the tantric faith; the rituals and worship modes are reflected in the sculptural art on the exteriors of the temples. Erotic sculptures in large number appear along with Vaishnava, Saiva, and Sakta themes and representations. The sculptures are marked by superb craftsmanship with sharp features — the nose and eyes are angular. The images are in neat profile and tall, and imbued with dynamic movement, flexibility, and sophisticated postures. The technique is one of undercutting in high relief.

Chalukya, Pallava and Rashtrakuta Sculpture

The South Indian sculptures are best represented in the dynastic rule of Chalukya, Pallava, and Rashtrakutas. The period of these three empires is marked with political differences and upheaval. But in the field of art and architecture, they complemented each other in many ways. So, we will try to understand the stylistic features by looking at them as coming from one source and manifesting in fine works of art. All these dynasties followed three religions: Hinduism with Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta development, Jainism, and to some extent Buddhism. The creation of sculptures depended on the interest of the ruler.

The Chalukyas used the locally available sandstone for architecture. For the sculpture in structural temples they selected superior quality stone so that the form emerges to their expectations. The Pallavas used the granite boulders at Mahabalipuram to carve the images in natural grace and beauty. Also, for structural temples, they used sandstone. The Rashtrakuta sculptures are very big in size, and carved mainly in bas-relief technique because they are carved in volcanic rock, and their creations are gigantic and emotionally expressive.

The low-relief, high-relief and bas-relief techniques were used depending on where the sculptures were to be carved. They achieved standardization in relief carvings. Round sculptures such as gigantic bulls and elephants are few, and carved using the entire boulder. The carvings are natural and provide beauty to these round sculptures.

The Dravidian, or dakshinatya (southern), architecture saw its stage-by-stage development during this period. Accordingly, the images of Shiva in dancing and iconic forms were portrayed on the walls of the temples. Dancing Shiva at the Badami Shaiva Cave is the earliest historical illustration of dancing Shiva in accordance with Bharata Muni’s Natyasastra tradition. From here, the journey of Nataraja sculptures begins in the history of dance and sculpture. In all these sculptures, the sculptors achieved movement in the figures. They are highly expressive.

Vaishnava imagery is depicted in the Vaishnava caves at Badami, where the sculptures of Trivikrama, Varaha, and Narasimha incarnations created in bas-relief technique are very expressive and bigger than life-size. The Anata figure in this cave is the only one of its kind. Vishnu on Ananta at Badami Vaishnava Cave is a superb sample of the illustration of Vishnu seated on the gigantic, coiled naga — the serpent. The four-armed Vishnu with the shankha (conch shell) and chakra (wheel) in his upper hands, and the lower hands in the abhaya (reassurance and safety) and varada (boon dispensing) mudras (ritual gestures). The Lord is seated in ease. The gigantic rock has been transformed into a great work of art. The Durga Temple Aihole has few Vishnu sculptures of high quality. Similarly, the incarnations of Vishnu sculpture is expressed in the Pallava style at the Kailasanatha and Vaikuntha Perumal Temples at Kanchipuram, and in the caves at Mahabalipuram.

Delicacy in carving is the striking feature of Chalukya, Pallava, and Rashtrakuta styles. For the first time in these three styles, the Devi figures — Lakshmi, Sarasvati, Parvati, Mahishamardhini, Saptamatrukas, and Ardhanari — are depicted in natural grace. The attendants, dancers, and musicians decorate the units of architecture in all these styles. One very interesting feature of these styles is the large bulls placed in front of the temples. In the temple architecture, there are images in the round such as elephants, tigers, lions, bulls, and horses. For the first time, Hindu narrative is present in these sculptures. The episodes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata are depicted on the pillars of Virupaksha Temple, and on the huge screens of Ellora Kailasa Temple. These are carved in relief. Similarly, narrative content from the Ramayana and Mahabharata is seen on the boulders of Mahabalipuram.

Through these styles, the iconography of the gods of the Hindu faith has put them on firm basis. The agamashastra was followed in creating the images. They are proportionate and life-sized. The sculptors of Chalukyan times are very dance conscious. They have applied the art and science of dance in creating sculptures. This tradition later becomes very common and the sculptors used dance and music in all possible ways. Because of this, the architecture received fresh subjects.

Sculpture under the Cholas is complementary to their architecture. Sculptural art has grown along with the design and plan of the architecture. The Chola artists followed the earlier tradition of the art of stone-cutting, which was in use from about 600 C.E. The stone carving of Pallava period was replaced by the Chola sculptors. The sculptures were carved according to the themes and techniques mentioned in Shaiva Purana (religious text dedicated to Shiva). Very rare and interesting themes have been portrayed in the temple and their premises. The sculptures in the Shikhara (tower) narrate the stories of Shiva Puranas. In the Chola period, we find different kinds of sculptures. Stone was the main material. Colored stucco figures were sometimes used in sanctum. Similarly, stone lingam, and bulls of gigantic size were carved and worshipped in the temples.

We find relief and round sculptures in Chola times. The stone they used was good quality granite, which is very hard and long-lasting. Because of the quality of the stone, they were able to create quite large sculpture. The other material they used was different metals. The mixture of metals in right proportion is known as bronze. It was known as panchaloha and the images were made by using five metals — iron, lead, brass, copper, silver, and even gold.

We find more relief sculptures adorning the temple walls and niches. They were carved following the instructions of agamashastra. The subjects are the seated goddesses Sarasvati, Lakshmi, and Parvati. Individual sapta matruka (seven mothers) sculptures are worked in three-quarter round. Relief technique is used in decorating these sculptures. It is a tribute to the greatness of the art and skill of the sculptors that such artistic images were carved into such a hard material as granite. Freestanding, large-sized lingams and bulls were carved in the round. The sculptors have created some wonderful sculptures in the round. Many of them are found in the museums all around the world.

Chola Bronzes

Another class of Chola sculptures is the world famous Chola bronzes. Chola artists had mastered the science and art of making metal sculptures. Their technique is followed even today, and has continuity with that of the Indus Valley Civilization period. The Pallavas also knew bronze casting techniques. Many bronze sculptures of the Pallava period still exist today.

The Chola sculptors improvised the technique and art as they did with stone sculptures. This is the period which witnessed the high-water mark in the art of bronze casting. Bronzes were produced in large number. They were used in temple processions replacing the god in the Sanctorum. They were carried by inserting a bamboo rod into the hole made during the sculpture’s casting. Most of the sculptures have inscriptions written in Chola character. Because of this, dating of the sculptures is possible. In most of the major temples, these bronzes were donated by the patrons, and they were displayed in the galleries of the temples. Today, they are displayed in museums inside and outside India. Even today, all over the world, there is a great demand for Chola bronzes.

The Chola sculptures have very distinctive features. The Chola artists have retained the image making traditions of the Pallavas. The figurative sculptures are strong and elegant, with a subtle rhythmic quality. Due to this treatment, the Chola sculptures are pleasingly delicate in outline. Humanism and freedom of pose are the two significant features that elevate Chola carvings to the status of great art. They are naturalistic, and display an elaborate treatment of decorative details. Such details are suggested in Pallava images by soft lines and low-relief which often merge in the modeling; in Chola style, the relief is high and bold. The jewels are worked in details like katisutra, hara, and kanthi (neck ornament). It is in sculptures of this period that the skandamala (shoulder tassel) appears for the first time. Chola sculptures display interesting variations in style and decorative details. Some figures, in terrifying attitude also contributed for the stylization of Chola sculpture. The composition is generally large to suit the proportion and size of the temple.

Generally, the images are in bold relief. Figures are shown frontally, and profiles are rare. They are carved with the iconography in mind. It is in the beginning of the early Chola period that the Anandatandava mode of dance is crystallized, and is shown in stone and metal. In the representation of this and other themes, minor variations are found. The metal art was highly patronized during the later Chola and Vijayanagar periods as well; but examples of these periods do not show dynamic and rhythmic movement so characteristic of Chola bronzes. The later Chola sculptures lose the natural grace and plasticity of earlier times. Some of the specimens of this period are poor in depth and lacking in modeling.

Hoysala and Vjayanagar Sculpture

The Hoysala architects used soft stone for the construction of temples. It is gray or gray-bluish, soft stone, which is very suitable for carving. We do not have examples of other types of stone or metal used for sculptures in Hoysala period.

In the Hoysala style, the sizes of the sculptures are small compared to Chalukya, Chola, or Rashtrakuta art; the relief in bands and friezes is sharply cut, resembling stencil cutting. The wall portions have the sculptures which are in comparatively high relief. Usually, three quarters of the image emerges out of the wall. The highest achievement of the Hoysala sculptors is beautiful, rounded sculptures. Gigantic bulls in the Halebid Temple are proof of the sophistication of the round sculptures. They are rare pieces — perfect anatomically, in posture, decoration, and in depiction of the animals. The other series of round figures are the bracket figures — madanikas (celestial nymphs), and salabhangikas (sculpture of a woman standing near a tree grasping a branch). The beautiful bracket figures of Kalyana Chalukyan, and the salabhanjika sculpture in National Museum, Delhi, and in the temples of Kuruvatti are the excellent artistic pieces of this phase, and are the models for Hoysala bracket figures. The Hoysala sculptors acquired mastery over creating the salabhanjika figures. In Belur, there are forty-two bracket figures enhancing the beauty of the temple. Some of the most famous museums in the world have Hoysala sculpture in their collections.

The main feature of Hoysala sculptures is its attention to exquisite detail, and skilled craftsmanship. They carve the stone like a jewel piece. The units of the tower over the temple shrine (vimana), are delicately finished with intricate carvings, emphasizing the ornate rather than the form and height of the tower.

Hoysala art is like an abode of carvers. The highest degree of crisp carving is the characteristic of this style. The Hoysala period reached its zenith in the art of jewelry. This concentration of ornamentation distinguishes Hoysala sculptures from other schools of sculpture. The Hoysala sculptures can be identified very easily as the jewelry is the prerequisite decoration of the sculpture of this period. Even the musical instruments, and attributes of the hands of the images are carved like jewels. Hoysala sculpture is often criticised as being overly ornamented. In spite of these defects, the Hoysala style of sculpture is distinct. It is impossible for anyone to count the varieties of garlands, necklaces, bands, bangles, earrings, bracelets, shoulder ornaments, anklets, and girdles on the Hoysala sculptures. Some of these highly impressive sculptures include Ananda Tandava (a dance of Shiva) Gajasura Samhara (Shiva as destroyer pf the elephant demon), Nataraja (Shiva as cosmic destroyer dancer) and Andhakasura Samhara (associated with a band of musicians). Dancing Sarasvati, Ganapati, Krishna, Parvati, Bhairavi and Mahishamardini are some of the very distinctive sculptures.

We are fortunate to find the names of the sculptors beneath some of the sculptures. Dasoja and Chavana were the chief sculptors of the Belur Temple. Padari Malloja, Mallianna, Nagoja of Gadag, and Chikkahampa, Kalidasi, Maba and Haripa and Mallittamma are the prominent sculptors who contributed to the glory of other Hoysala temples.

The legacy of sculpture, architecture, and painting of the Vijayanagar Empire influenced the development of the arts long after the empire came to an end. The artisans used the locally available hard granite because of its durability, since the kingdom was under constant threat of invasion. While the Empire’s monuments are spread over the whole of southern India, nothing surpasses the vast open-air theater at its capital, Vijayanagara. Granite was used for carving the sculptures. Stucco and metal sculptures were in great use.

Relief sculptures are plentiful in the Vijayanagar style. The story of the Ramayana is beautifully narrated through the relief sculptures on the walls of the Hazara Rama Temple. These beautiful sculptures depict the life of Rama. Episodes from the Ramayana are delicately sculptured on the exterior of the temple. Whenever there was a need for many images with popular narrative content, the relief sculptures were highly recommended, and perectly suited to the task. The “Great Platform” (Mahanavmi dibba) has relief carvings in which the figures have fine facial features.

The sculptors were specific in carving the round figures. The rounded images cannot be produced during a short period of time. The Rayas (rulers) commissioned huge round sculptures such as the Narasimha (an avatar of Vishnu), two Ganesha (elephant diety) figures, the bull, and the Gommatesvara images at Karkala and Venur. The massive, solid granite rathas (chariot) — with the huge wheels in the open courtyard of the Vitthala Temple — is a round sculpture, as well as architecture.

Vijayanagar style is the last in the development of Indian art and architecture. After this, India has never seen such glory in cultural life.

The hallmark of the Vijayanagar style is the ornate, pillared halls in the temples known as Kalyanamantapa (marriage hall), Vasanthamantapa (open-pillared halls), and the Rayagopura (tower). There is more about the architecture of the Vijayanagar Empire under the lesson “South Indian Architecture”.

Another element of the Vijayanagara style is the carving of large monoliths such as the Sasivekalu (mustard), Ganesha and Kadalekalu (ground nut), Ganesha at Hampi, the Gomateshwara statues in Karkala and Venur, and the Nandi (bull) at Lepakshi.

The art of sculpture and painting had attained a very high degree of excellence during that period. The typical lofty gopuram (tower) is covered with excellent sculptures.

The image style is indigenous, and followed the agamic (scriptural) specifications particularly when the images were carved for the purpose of rituals.

The type of sculptural compositions was preferred in Vijayanagar Imperial style. By the arrangement of numerous figures in a pattern, suggesting movement and expansion, the main figure seems to grow under the onlooker’s gaze. This treatment and approach was not the main concern of the Vijayanagar artists, nevertheless, small-scale, individual figures are the features of this style. They are included in the architecture where the aspirations of commoner and aristocrat meet to experience the divine purpose of art.

Indian sculpture is the product of Indian culture. The sculptural tradition primarily emerged from folk level in villages. The potter’s wheel is the first instrument of sculpture — turning the clay into pots and dishes. In the beginning, images were created in clay using simple techniques; later these became the techniques of creating terracotta art. The images were made out of fine clay, and then baked in the kiln so that the objects did not dissolve when they came in contact with water. Sculpture as an art form progressed into many styles during historical times. Many sculptures of gods and goddesses were created in sculpture, metal, wood, and ivory for the purpose of worship.

Bibliography:

S.P.Gupta & Shashi Prabha Asthana, Elements of Indian art, Print world II Edition Delhi 2007

Agraval V.S. Indian Art, Varanasi 1965

Banerjea, J.N Development of Hindu Iconography, Calcutta, 1941

Nandagopal Choodamani, Arts & Crafts of Indus civilization Aryan Publications, Delhi 2006

Nandagopal Choodamani, Manjusha – Art Genre, Dharmasthala, 2000

Coomaraswamy, A.K. History of Indian and Indonesian Art New York 1965

Sarasvati S.K, Survey of Indian Sculpture Delhi 1970

Shivaramamurti,C, The Art of India, Paris 1970

Pashupati seal of Indus Valley

Mother Goddess Indus Valley

Didarganj Yakshi Msurya Sculpture – Patna Museum

Pillar Capital of Ashoka – Sarnath Mauryan Sculpture

Gandhara School Bodhisatva

Buddha Mathura School

Ganapati Hoysala Sculpture – Halebidu

Sheshashayi Vishnu Deogarh Gupta

Buddha Sarnath Gupta

Buddhist Stupa, Amaravati School

Natya Mohini Chennakesava Temple Belur

Darpana Sundari Chennakesava Temple Belur Hoysala

Relief sculptures – Hajara Ramasvamy Temple Hampi

Pillred Mantapa with sculptures Ranganatha Temple Sri Rangam

Pillar sculptures Vijaya Vitthala Temple Hampi

Chariot Vijaya Vitthala Temple Quadrangle Hampi

Vishnu in a niche Pala, National Museum collection Delhi